After five years of meticulous digging, uncovering three layers of buildings in the ancient Saharan town of Garama – a town inhabited from 400BC to 1937 – David Mattingly and his team made a dramatic and unexpected denouement. “In the town’s extraordinary 2,500-year-history,” Mattingly told me, “what stands out is that the period of the Garamantian civilisation was the time of greatest material well-being; the Garamantes ate better than most subsequent inhabitants and had a wider range of locally manufactured and imported goods.”

That is at odds with the prevailing view of the Garamantes as fragmented bands of beleaguered desert dwellers, and only now, after many years of archeological research, is the true extent, power, and sophistication of the Garamantes beginning to emerge. The Garamantes prospered in the inhospitable hyper-arid terrain of today’s Fezzan region of Libya, and from Garama, the capital they founded in 400BC, they controlled an area larger than the UK for a thousand years. Yet the Romans characterised them as backward and uncivilised, all deceitful propaganda that might have had something to do with the fact that the Romans never managed to conquer the Garamantes. Now David Mattingly is seeking to “redress” the historical injustice by identifying the Garamantes kingdom as “the first Libyan state.”

“We have solid evidence now to identify the Garamantes as a state and a civilisation,” Mattingly elaborated. “Past researchers have been cautious about making this evaluation partly because of negative press by Greco-Roman writers who depicted the Garamantes as a troublesome tribe of armed brigands, pastoral nomads living in scattered huts and tents, without political and social sophistication. It was more palatable for Romans to believe in the stereotype of the ‘barbarian other’ rather than address the complex reality of a powerful desert kingdom. Yet the archeological evidence we have now shows the Garamantes as skilful agriculturists, and practitioners of advanced technologies such as pottery-making, metallurgy, glassmaking, salt-refining, and producers of semiprecious stones. Their society was complex, hierarchical and well-organised; they had a written script. In other words, they fulfilled all the criteria that define a ‘civilisation.’”

The Garamantian civilisation arose at the behest of an environmental catastrophe – the sudden failure of rainfall 5,000 years ago. “The desert has oscillated between wet and dry epochs five times since the Pleistocene,” told me Giuma Anag, a Libyan archeologist. “In the wet periods the desert received tropical rains, and a vegetation corridor formed between the Mediterranean coast and sub-Sahara Africa. There were forests of juniper, and animals such as elephants, lions, giraffes, and rhinos.”

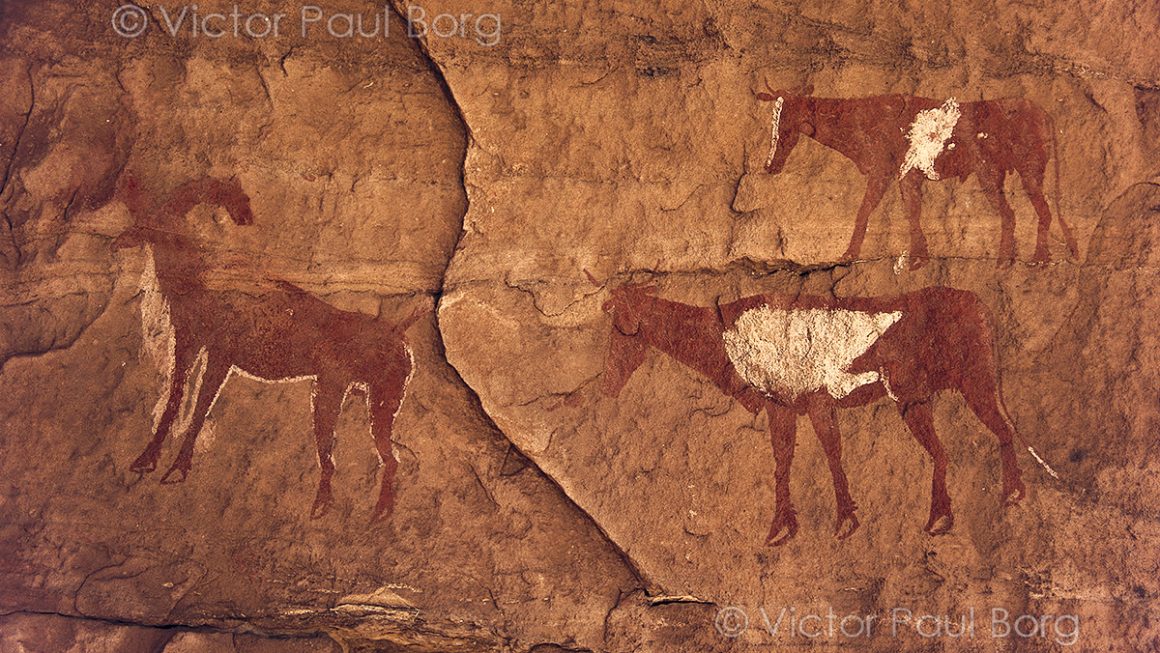

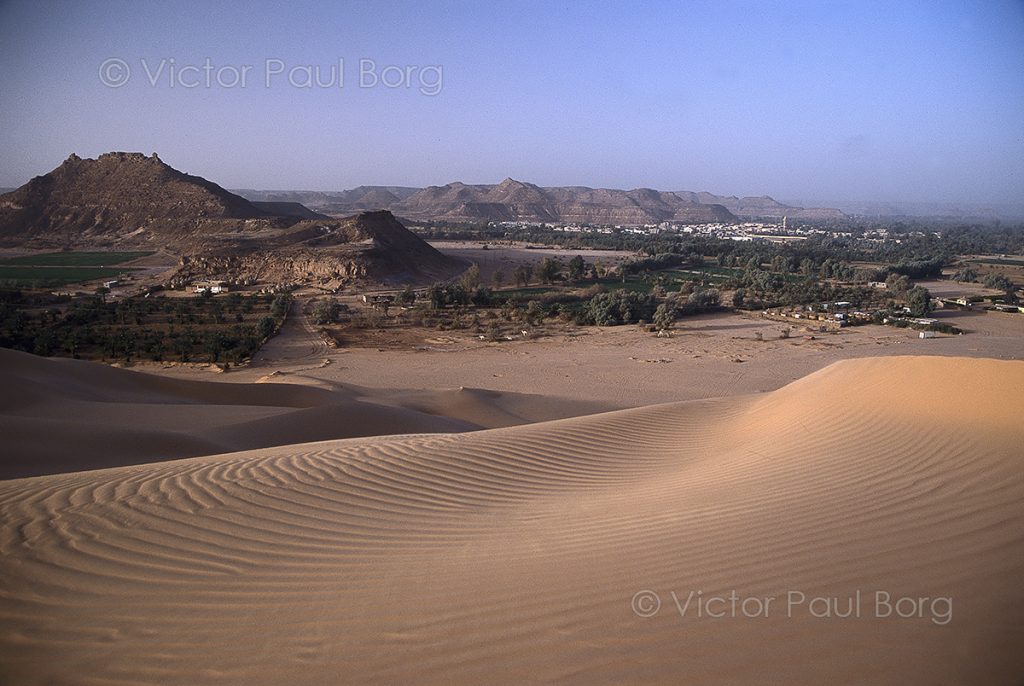

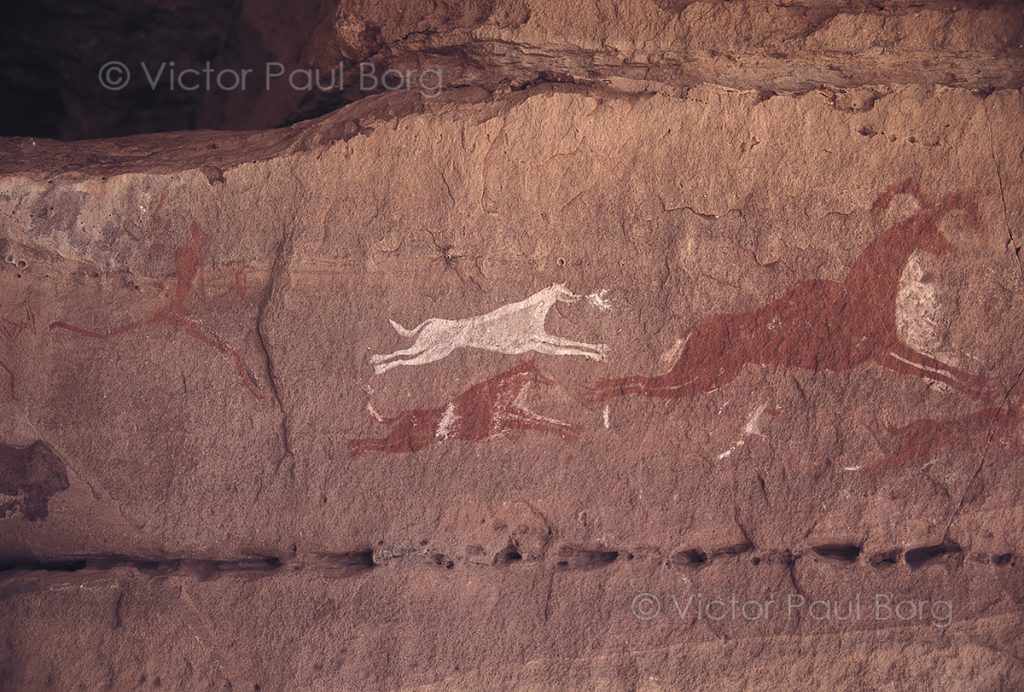

It’s a lost world depicted in the rock art that is ubiquitous throughout the desert; the paintings or petroglyphs, created between 2,000 and 10,000 years ago, show animals, hunting scenes, epic battles, and human rituals. Then, as the rain ceased 5,000 years ago, the pastoral herding communities migrated to the valleys where water was available in lakes and springs, or in underground aquifers close to the surface. The wettest of these was Wadi Al Ajal (since the seventies officially called Wadi Al Hayat, meaning ‘Valley of Life’), a vast valley 200km long and 30km wide at its widest span, hemmed in by the purple-black ridges of Miseqt Plateau to the south and the endless sand dunes of the Ubari Sand Sea to the north.

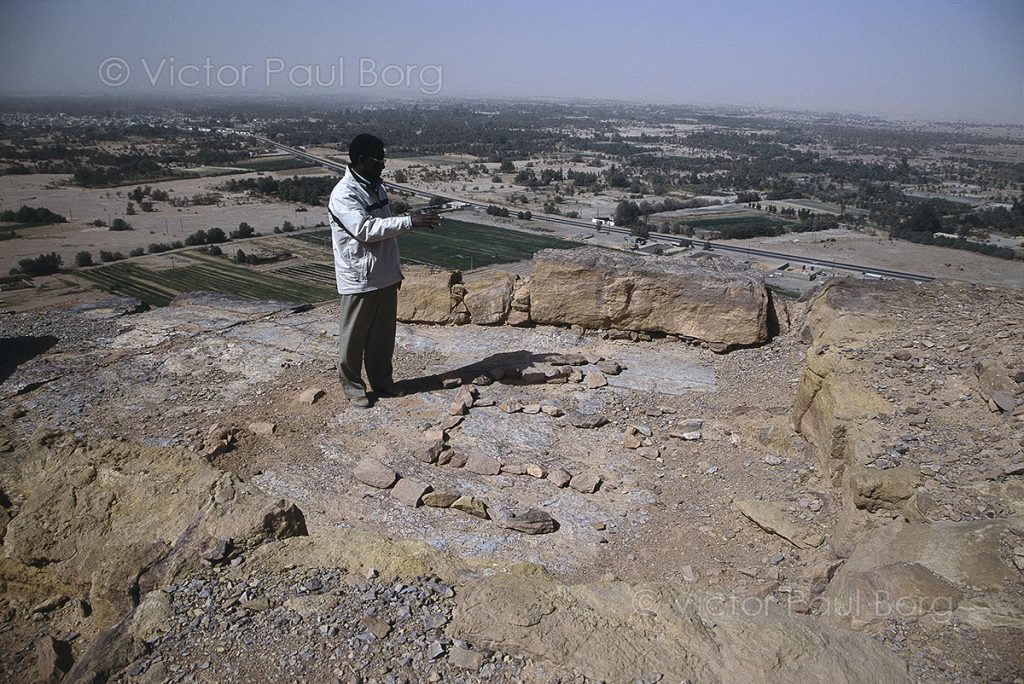

The Garamantes at first built settlements on the rocky bluffs jutting over the valley. These were fortified outposts, thirteen of which have been documented, including the classic fort at Zincechra which had a thick defensive wall built across the neck of the peninsula. It’s unclear how old these settlements are, but by 1,000BC the Garamantes had mastered agriculture and developed an impressive irrigation system known as foggara. This consisted of underground tunnels that channelled water outpouring from springs at the base of the escarpment throughout the valley. There were some 600 tunnels (with a combined length of 1,000km) interspersed with 100,000 shafts of up to 40 metres deep (from which water was hoisted up). The farmers used carts, horses, and camels, and they cultivated cereals, olives, grapes, and dates.

As the Garamantes flourished they founded Garama in 400BC. Houses were first burrowed underground. Then a second layer was built at ground level in the Classic Garamantian Phase (1–300AD) when temples and public buildings were constructed of large stones. Garama was at the geographical centre of Wadi Al Ajal; another 50 hamlets were scattered throughout the valley, and the Garamantes kingdom counted a population of between 50,000 and 100,000.

“Garama was famous for its salt,” explained Saad Abdul Aziz, head of the Fezzan branch of the Libyan Department of Antiquities. “There was plenty of salt around, and the Garamantes traded salt with people from the coast, Romans particularly, in return for amphorae and other things.”

Aziz and I were sauntering among the crumbling mud-brick walls and large-stone foundations at Garama. Then we drove to the Hattia Pyramids, a cluster of tombs that bloom in pyramidical structures of mud-brick. “There are about 100 of these pyramid tombs,” Aziz said. “It’s where important people were buried.” The commoners were laid to rest in simpler tombs, mostly found on the slopes and plateaux of mountains, recognisable by the mounds of dug rubble. There are about 120,000 of these graves scattered throughout the valley, and we could see many of them from Zinchecra, 300 metres above the valley floor.

From the high ridge at Zinchecra, Aziz pointed out the graves in the distance where excavations are currently taking place. These excavations are part of a new phase in Garamantian research that began this year and will last until 2011. Also led by David Mattingly – in collaboration with several universities in the UK – this ongoing research will focus solely on the exploration of tombs. “I am particularly interested in how the Garamantes defined their identity through material culture and ritual practice in these funerary contexts,” Mattingly explained from his office at the University of Leicester. “The cemeteries are an excellent place to investigate these relationships as it’s possible to compare the material identity of the cultural package represented by each burial with the ethnic identity implied by the palaeo-osteological studies.”

The first season of fieldwork has already yielded a trove of promising detritus. “We have found preserved textiles, leather and other material, all dating from 100AD to 300AD,” Mattingly chirped. “What we are retrieving will be the largest collection of ancient textiles from the Sahara outside Egypt and Sudan.” They also found imported things such as Roman amphorae, fine pottery, oil lamps, as well as an assortment of African relics that includes wooden headrests, ochre, incense burners, and decorated gourds. “Many of the burials,” Mattingly added, “contained beads in a variety of materials – ostrich eggshell, glass, semiprecious stones such as carnelian (red) or amazonite (turquoise), ebony – and some of the beads appear to have been stitched onto textile garments. We also have fragments of quite elaborate sewn or plaited leatherwork, some dyed red. These finds are going to transform our knowledge of what the Garamantes looked like.”

Yet Mattingly and his team are also in a race against time – urban sprawl, quarrying, and farm-expansions are encroaching on the burials. In theory all archeological relics are legally protected; in practice Aziz lacks the resources necessary to stop the destruction. "When the farmers find something, they smash it up because if they inform us we would stop them," Aziz said. "I had a farmer in my office this morning who wanted to extend his farm towards Zincechra. We stopped him and compensated him for his loss. Sometimes farmers aren't aware of what they are destroying – they don't recognise the archeological importance of foggara for example."

When we went looking for a foggara that Aziz knew of, at a farm off the road, we found three illegal immigrants from Niger making cement bricks in a yard. They said they had never seen a shaft on site, and Aziz realised that the shaft had been buried by the brick-making enterprise. "Our problem," Aziz lamented, "is that we lack the manpower to protect the sites. It's a large area, and there are graves scattered everywhere, so it's quite impossible for us to keep an eye on everything."

The expansion of farms and large agricultural projects, something the government encourages, is also depleting the underground aquifers. “The water table has receded from 3 metres below ground in the 1970s to 120 metres in the nineties,” Aziz said. “Now they are digging bore holes 200 metres deep in some places before they hit water.” The drop in the water table has had a dramatic effect around the ancient town of Garama: the reed-fringed ponds and date palms of yesteryear are now a wasteland of skeletal trunks. "When I was young the palms were so dense that it was dark in the midst of the grove,” Aziz said soberly. “Now I feel great sadness each time I come here.”

There’s a lesson to be learnt about this from the eventual demise of the Garamantes. By 200–300AD the population growth was depleting the groundwater; and this, coupled with the decline of the Roman Empire (which resulted in diminishing trade), eroded the resourcefulness and prosperity of the Garamantes and exposed their heartland to attack and domination. “Over-exploitation of the non-renewable water,” Mattingly explained, “necessitated a switch to a different form of irrigation that was far less efficient and that resulted in a much smaller area under cultivation – this had knock-on effects for the population base that could defend the kingdom and intimidate its neighbours.”

Climate Change and Civilisations

“An understanding of how the climate system works,” said Nick Brooks, a visiting research fellow at the University of East Anglia, “will help us model future climate change and make tentative predictions.” This has been a separate component of desert research, the study of climate and environmental change.

Climate change in the Sahara Desert has a long history of dramatic fluctuations between wet and dry periods. Nick Brooks’ team has even found evidence of the existence of an ancient lake (Lake Megafezzan) the size of the Czech Republic in the central Sahara. Since then there have been various dry and wet epochs, relating to glacial changes; the last wet period, between 10,000 and 5,000 years ago, was preceded by an arid period between 60,000 and 10,000 years ago when, it is thought, human habitation in the central Sahara ceased altogether. The latest arid period started 5,000 years ago. “Starting from about 9000 years ago,” Brooks explained, “solar radiation became less intense until this ‘solar forcing’ was too weak to sustain the monsoon. So the monsoon then failed, and the collapse is likely to have been sudden – it may have been hastened by a ‘climate shock’ associated with a periodic cooling of the north Atlantic (conditions typically associated with aridity in the northern hemisphere subtropics), and a collapse of the vegetation systems over North Africa, which probably sustained a weakening monsoon through the recycling of moisture.”

Since 2002 Brooks has led a parallel research project in the Western Sahara. The team has found no evidence of a great civilisation as the Garamantes in the Western Sahara; the preliminary picture is of pastoralists who congregated in the wetter valleys as the world around them dried up. “Today we are often told that pastoralists are among the groups most vulnerable to climate change,” Nick said. “In fact they are among the best equipped to deal with highly variable conditions, provided they are not marginalised and pushed to unproductive areas as has happened in recent historical times.”

“We also tend to believe that agriculture and civilisation arose from natural human progress, and were made possible by the benign post-glacial climate of the past 10,000 years. However, when we look at what was happening in the cradles of civilisation, we find that all the great civilisations of antiquity emerged in areas experiencing desertification. Civilisation was born in times of climatic hardship, and was based on the same sorts of changes that we see in the prehistoric Sahara – more social inequality, more hierarchy, and greater competition as people were squeezed into smaller geographical wet areas.”

Now global warming is expected to change the climate in the Sahara again. Nick explained: “Some researchers believe that the present aridity will be partially reversed by global warming. Some models suggest that up to 25 percent of the Sahara could become green, and recent rainfall trends at the southern fringe of the Sahara are consistent with these projections, but it is still rather early to celebrate the re-greening of the Sahara. This time round we don't really have any precise past analogues, so we are entering unfamiliar territory.”

© Victor Paul Borg. This article first appeared in the magazine of the British Royal Geographical Society.