“The great mystery is how and why the jars were carried so far from the source,” Khamman Phimmasan was saying. “It’s a formidable haul.” Khamman, the official in charge of historical heritage in Laos’ Xieng Khoung province, was flitting breathlessly among the pine trees on the mountainside at Phukeng, pointing out the unfinished megalithic stone jars that have lain here for two millennia. His excitement is palpable: this highland plateau littered with prehistoric monuments is finally getting the international attention it deserves, an upsurge in research and development, and preparations for World Heritage listing, setting the province on a trajectory of fame and affluence. At Phukeng dozens of mortuary jars are scattered on the alpine slope in various stages of completion. It’s an enigmatic sight and a scenic spot that the tourist board is eager to open to tourists by 2008. “It could have taken thirty days to make a jar,” Khamman conjectured.

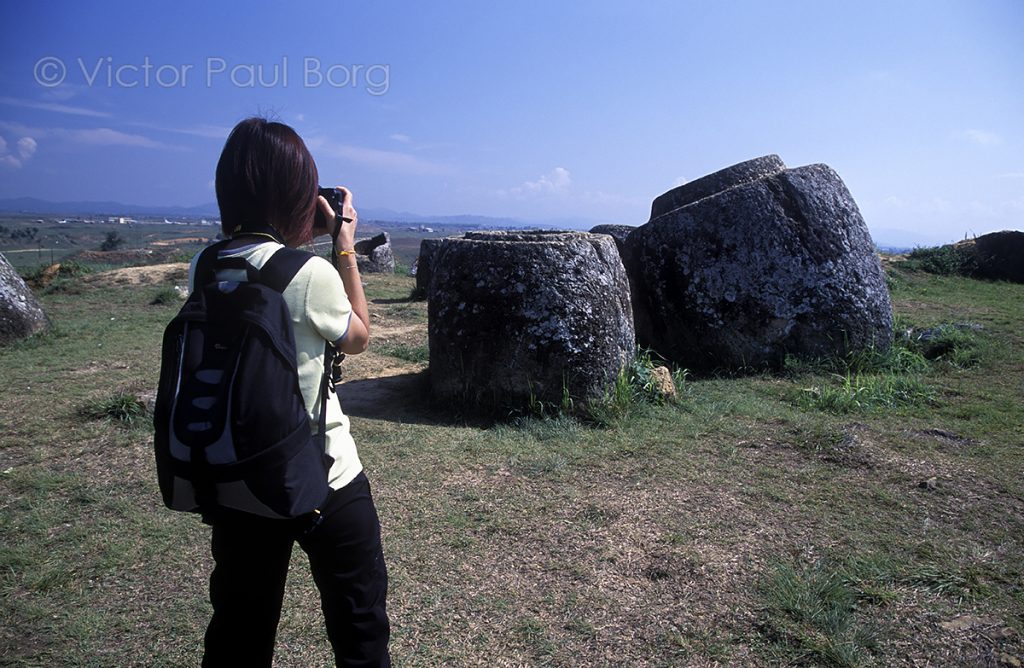

The jars were carved from boulders using hammer and chisel, then transported 8km away to a burial site now known as Site 1, where there are 334 jars. The largest mortuary vessel at Site 1 weighs 6 tons, and most are between two and three metres high – hence the transportation feat. From our viewpoint at Phukeng, Site 1 lay somewhere in the hazy distance, across the undulating grassy landscape webbed by streams and dotted by pine trees, somewhere beyond Phonsovan, the provincial capital, close to the faint mountains that serrate the horizon.

Discovered by Khamman and Thongsa Sayavongkhamdy, Laos’ pre-eminent archeologist, the prehistoric site at Phukeng was among the first – and still the largest – of fifteen jar-making sites found since 1998. These finds and many more have now been plotted on a computer GIF mapping system, allowing archeologists to chart the course of the stone monuments. Linking the dots revealed patterns that might indicate the scatter of settlements or trade routes at the time. But the discoveries have raised new vexations too. To start with, why were so many jars at Phukeng never completed?

Discovered by Khamman and Thongsa Sayavongkhamdy, Laos’ pre-eminent archeologist, the prehistoric site at Phukeng was among the first – and still the largest – of fifteen jar-making sites found since 1998. These finds and many more have now been plotted on a computer GIF mapping system, allowing archeologists to chart the course of the stone monuments. Linking the dots revealed patterns that might indicate the scatter of settlements or trade routes at the time. But the discoveries have raised new vexations too. To start with, why were so many jars at Phukeng never completed?

“Two possible reasons,” Khamman answered. “Construction could have been abandoned after the rock was deemed unsuitable, or the time for making jars had come to end.”

Both reasons raise more questions still. And no one knows who were the people that practiced such extravagant death rites, and why they vanished. Yet their impressive legacy – hundreds of stone mausoleums of sorts clustered on the crests of hills and mountains – conjure a civilization that was prosperous, confident, and culturally advanced.

“We know that the plain was a strategic trade hub at the time along a trade route that extended from India to China,” told me Samlane Luangaphay, another Lao archeologist. “We also know that today’s inhabitants are a new people, and the culture at the time was different and complex. Now we need to do more extensive research to come up with more answers about the ‘who’, ‘why’, ‘when’, and ‘how.’”

“It’s one of the most intriguing and enduring puzzles of Southeast Asian prehistory,” UNESCO says in a report. The aptly-named Plain of Jars is already on the tentative list of new World Heritage Sites, and for several years UNESCO has been funding a multi-pronged project – research, heritage management, and tourism development. A still-ongoing survey has already doubled the number of previously-recorded archeological sites. The tally now stands at 1,900 jars in 52 clusters, plus fifteen jar-making sites. “Some sites are very remote,” told me Rik Ponne, a UNESCO consultant, in his Bangkok office. “In some cases we had to trek into the mountains for two days, so I am sure we’ll find more jars.”

The jars were initially documented by the French archeologist Madeleine Colani in the 1930s. She studied the three main sites – Site 1, 2, and 3, which together comprise more than 500 jars, and constitute the main tourist attractions in the province, situated within a short drive of Phonsovan. Her theory remains current among archeologists: that these stone vessels functioned in mortuary rituals that could have developed as a cultural precursor, or in parallel, with the Buddhist concept of reincarnation. The idea is that the dead body would be placed in the jars until it decomposed to its ‘purity’ or ‘essence’. Then the body would be cremated – Colani found a cremation cave at Site 1 – and the remains buried in a pot alongside certain personal or symbolic possessions.

Colani’s work was followed by decades of conflict, and the isolation of the communist years, putting a hiatus on research. Eventually the country belatedly embraced tourism in the early nineties, and the jars became a major tourist allure. The number of foreign visitors hit 24,000 in 2005, up from 15,000 in 2004. World Heritage status is expected to open the tourist floodgates by 2008 or 2009.

In the past few years UNESCO has instituted various management and tourism projects. Community-based structures to monitor and protect the prehistoric remains are now in place, and five new tourism pilot projects have been launched, all based on clusters of attractions – natural, cultural, and historical. “At present we’re helping the authorities prepare a nomination dossier to achieve World Heritage status,” Rik Ponne explained. “We need more research, and we need to implement a comprehensive management plan to ensure that the heritage sites, once listed, are actually preserved.”

In the past few years UNESCO has instituted various management and tourism projects. Community-based structures to monitor and protect the prehistoric remains are now in place, and five new tourism pilot projects have been launched, all based on clusters of attractions – natural, cultural, and historical. “At present we’re helping the authorities prepare a nomination dossier to achieve World Heritage status,” Rik Ponne explained. “We need more research, and we need to implement a comprehensive management plan to ensure that the heritage sites, once listed, are actually preserved.”

But archeological research has been hindered by the detritus of the American war. The province is littered with unexploded bombs. Thongsa Sayavongkhamdy and Khamman took great personal risk in the late nineties when excavating burials among the jar fields. “We found bones and other organic material, as well as bracelets and necklaces made of glass, a smoking pipe, and an earthenware vase,” Khamman elaborated. “However, it’s uncertain whether these burials took place at the same time the jars were made.”

That’s because carbon dating showed the excavated material to be dramatically beyond Colani’s timeline. Colani used cultural and development parallels in the region to extrapolate that the jars were made between 500BC and 500AD. Yet one of Thongsa’s dates goes back to 3,500-4,000BC, and another as late as 1,000AD. Analysis by the Belgian archeologist Julie Van Den Bergh, a UNESCO consultant, of some charcoal material from another burial also registered the early date of 3,000BC.

“I’m asking myself, ‘What is going on?’” Julie said when I asked her about these dates. “Are the secondary burials older? It’s uncertain how the burials relate to the jars; there are too many unknowns. We really need more dateable material, and to review excavated material in comparison with new major research in the region.”

New major research is in the offing at Ban Phakeo, one of the most promising new discoveries – a cluster of 416 jars, the largest ever recorded, set at the crest of a desolate mountain – which I visited with Khamman. It is situated three hours walk from the nearest road, and half an hour’s walk from a small Hmong village. The site itself is surreal: hundreds of mostly-intact eerie jars scattered in hush forest, and a mountaintop vista of high contorted mountains straggling towards the horizon in every direction. It’s an idyllic resting place for the spirits of the dead, and the Hmongs believe so too – they have been burying their death in mound graves among the jars.

New major research is in the offing at Ban Phakeo, one of the most promising new discoveries – a cluster of 416 jars, the largest ever recorded, set at the crest of a desolate mountain – which I visited with Khamman. It is situated three hours walk from the nearest road, and half an hour’s walk from a small Hmong village. The site itself is surreal: hundreds of mostly-intact eerie jars scattered in hush forest, and a mountaintop vista of high contorted mountains straggling towards the horizon in every direction. It’s an idyllic resting place for the spirits of the dead, and the Hmongs believe so too – they have been burying their death in mound graves among the jars.

The Hmongs have been in these mountains for 200 years, and they believe, as other local inhabitants, that the jars were commissioned by a powerful ruler for the fermentation and storage of Lao Khao, the vernacular rice whiskey. As such they didn’t recognize the spiritual auspiciousness of the jars. They were formerly breaking jars to cover their mound graves, and sharpening their machetes on the jars. At the village – which has 28 households, and where we spent a fitful night sleeping on wooden beds – I noticed two grinding stones fashioned from jars, used to grind corn that is fed to the pigs. Now UNESCO is paying the villagers to stop the breakage and keep the vegetation trimmed down.

The area features on one of UNESCO’s five tourist circuits. It’s indeed one of Asia’s most spectacular new tourist sights, holding a triple allure: the village, the trek, and the jars. The jar cluster itself is doubly attractive as it conjures the idea of a lost civilization. The evocation is of mountains that were more densely inhabited at the time, an allegory about the rise and fall of civilizations, and nature taking over again – some trees have grown out of the peat that accumulated in the jars, the roots growing over the jars like rapacious tentacles. More urns are trailed along a path that continues along the ridges over many kilometres to Ban Na-o, near Site 1, and Julie theorises that this could have been a former trade route.

The area features on one of UNESCO’s five tourist circuits. It’s indeed one of Asia’s most spectacular new tourist sights, holding a triple allure: the village, the trek, and the jars. The jar cluster itself is doubly attractive as it conjures the idea of a lost civilization. The evocation is of mountains that were more densely inhabited at the time, an allegory about the rise and fall of civilizations, and nature taking over again – some trees have grown out of the peat that accumulated in the jars, the roots growing over the jars like rapacious tentacles. More urns are trailed along a path that continues along the ridges over many kilometres to Ban Na-o, near Site 1, and Julie theorises that this could have been a former trade route.

“How does a civilization with such an impact on the landscape didn’t leave more stories and legends, or more material evidence lying around?” Julie mused. “What were they doing? For how long? And why did they vanish? This is what we’re trying to answer.”

To that end Julie and her colleagues have already began digging the ground in earnest expectation.

An Explosive Legacy

The Plain of Jars’ strategic importance – a vast plateau surrounded by high contorted mountains – brought a deluge of American bombs in the sixties and seventies. The highland plain was a stronghold of the Pathet Lao, and a staging post of the Vietcong, and the American launched the heaviest aerial bombardment in the history of warfare. A staggering 13,000 sorties were dispatched every month, an assault so fierce that the 1,500 buildings of the then provincial capital were flattened in one day. “It was a very hard time,” told me Khamman, who was a young man living and studying in caves.

The legacy is still explosive. “About 20,000 people have been maimed or killed since the end of the war,” told me Dave Davenport, the local leader of the NGO British Mines Advisory Group (MAG). “And that figure is just for the people who turned up at hospitals.” MAG is one of two organizations – the other is UXO-LAO, the national organization – that have been clearing unexploded bombs for several years.

Farmers strike bombs when ploughing their fields, children blow themselves when playing with cluster bombs, and many people get hurt when scavenging for bombs for scrap metal material – a 500-pound bomb can fetch US$21, a lucrative prospect at a place where US$1 daily is considered a good salary. “The level of contamination is extremely high,” Dave explained. “For example, in just one village recently we removed 4,500 items.” MAG has also recently finished clearing the main jar sites, famously unearthing a 250-pound bomb from near one jar at Site 2.

The effects of the war have made Xieng Khoung’s 200,000 inhabitants the poorest in Laos. Now the tide is changing. Steadily-increasing tourism is fuelling something of a boom, and whole new swathes of Phonsovan are sprouting up. Improving infrastructure and impending World Heritage listing have instilled a palpable hope that the province will regain the prosperity enjoyed by its ancient inhabitants.

© Victor Paul Borg. This article first appeared in the magazine of the UK's Royal Geographic Society.