“Our pineapples are very productive,” told me Stuart Roach as he showed me around his farm. “I cut some pineapples yesterday that were 4kg heavy, and that’s something.” Ever since he had married a Kelabit and moved to Bario, Roach had revitalized his father-in-law’s abandoned paddy fields: he had restored the cottage that now serves as his home, he built a bathroom and cistern outback, he planted fruits and mixed crops, and he constructed two standalone bungalows for lodgers. Then he named the farm Libal Paradise.

Roach wanted to get into the tourist business, hoping to lure tourists to stay in Libal Paradise on natural retreats, and he had invited me to see what he had created. Now we continued through the three-hectare farm, walking past the fallow fields at the back that would become a future ‘bird sanctuary’, and then ducking down a path into the kelangas, a swampy forest that teems with birds and insect-gobbling pitcher plants. Finally we arrived at the riverbank where Roach’s guests would go kayaking, and then we doubled back looking for wild vegetables to pick up for lunch. “It’s not for everyone here,” Roach told me, “but this place is perfect for me.”

In a larger way, the Kelabit Highlands in the centre of Borneo are all about untrammeled nature and forest living. Trails radiate from Bario, the main settlement, to the 13 other Kelabit villages scattered in the mountains, and hikers can follow these trails in different combinations, for treks ranging from one to seven days of walking. Lodging is in longhouses or home stays, where you can count on the legendary hospitality of the Kelabit people, as well as their excellent cooking – premium Bario rice and the superlative pineapples are complemented by wild ingredients such as fishes, boar, deer, mushrooms, ferns, bamboo, ginger, wild fruits, and so on. Longer treks penetrate old growth jungle, and in Mount Murud – the high mountain that straddles the border between Malaysia’s Sarawak and Indonesia’s Kalimantan – I experienced the most raucous dawn chorus in ten years of outdoor travel in Southeast Asia.

It’s an experience shared by 400 other tourists that visited in 2008, a volume of tourists that was expected to climb steeply in 2009. Peter Matu, who is now building a private museum, told me: “This is the first year that I am seeing a regular inflow of tourists in the low season.” And Douglas Munney, owner of De Plateau Lodge, has seen the number of tourists increase by about eighty percent in three years since the launch of the Food and Culture Festival in 2005.

“Some stalls ran out of food last year, so I guess that’s a measure of success,” told me Dora Tigan, secretary of the committee that organizes the annual weeklong event which sees each Kelabit village put up a stall to compete for the best décor and food. “We like to say that the jungle is our supermarket, and the festival is a celebration of the Kelabit forest food.”

In tourism stakes, the festival has raised the profile of the Kelabit Highlands as an excellent rural destination. It’s also an opportunity to promote the indigenous variety of rice, which has a consistency that is fluffy and chewy. It’s already renowned as the top brand within Malaysia, and the production of rice is one of the two economic motors (the other being tourism) in the Kelabit Highlands. Around 350 rice farmers produce 400 tons annually. “The rice farmers get a good price,” told me Peter Matu. “But in the end, once high labour and transport costs are paid off, the profit only amounts to a couple of hundred ringgit every year.”

There is no road to Bario, and the only way in or out is on the twin-otter planes that fly twice daily. Bario is a settlement of 800 inhabitants that sprawls on a plateau, and transport within Bario is in six pickup trucks that crawl at the pace of a jog on the rutted roads (bringing in the vehicles entailed driving them to the point where the logging road peters out, then stripping them apart and transporting the parts bit by bit on boat). Other Kelabit villages scattered in the mountains have to make do with buffalo transport along a network of forest tracks.

This is a boon for visitors who seek an escape from cities and cars. And, after all, the reason why forest food has remained the staple food – wild food has to be gathered and hunted – is because imported packaged food is expensive (some families in Bario fly to town every month just to go shopping for food). But for the Kelabits, the transport logistics are simultaneously a blessing and curse, a situation that has preserved their peaceable idyll and at the same time kept them underdeveloped.

The Kelabits were completely cut off from the outside world until the arrival of British forces led by Tom Harrison in World War II. The soldiers parachuted into Bario, and the Kelabits watched them from the longhouse at Bario Asal. “My father told me that when the soldiers approached the longhouse, they tied their guns to ropes and dragged them on the ground behind them in order to demonstrate that they didn’t come to fight,” told me Peter Matu as we sat in the same longhouse, and I gazed out of the window trying to conjure what it would have been like then.

Later the Kelabits fought alongside the British against the Japanese that had advanced as far as Pa Lungan, four hours walk away from Bario. Harrison stayed with the Kelabits after the war, spreading an infusion of western influence, and missionaries did the rest. The Kelabits became fervent Christians, abandoning their previous lurid animism and head hunting and megalithic culture (the highlands still have many dolmens and remains of jars in which the dead were interred). They perceived Christianity as liberation from the capriciousness of head-hunting and animist superstitions, and Sunday is now an important day: the old wear their best on Sunday, donning their colourful costumes and the opulent traditional earrings that weigh 600 grams each.

During my visit I stayed in Bario Asal, the oldest extant longhouse in the Kelabit Highlands. It’s a splendid wooden structure divided in three long sections: the communal kitchen, a hall for social or religious gatherings, and the private sleeping quarters. A longhouse engenders a community that’s inclusive and egalitarian and harmonious, and families mingle in the communal kitchen, sharing food and yarns. Just before my visit, Peter Matu had collected funds from the longhouse inhabitants and built a mini-hydro power plant that provided electricity for the longhouse.

Yet most people in the longhouse were old people, and it was the same in the other villages I trekked to. Many things are in fact changing. The traditional body markings of dark tattoos and elongated earlobes will die out with the old generation, and the younger generations’ allegiance to Christianity or Kelabit customs or the longhouse is weakening. Most young people move to the cities and never come back, and the population has been dwindling for some time, currently down to around 1,800 inhabitants.

Development has been slowly trickling in. The University of Malaysia has instituted a project to improve Internet Communications Technology as a way of overcoming physical isolation with internet connectivity. Bario now has satellite internet, and mobile phone reception had been established just three months before I visited. Bario even got its own promotional website. “We’re getting many online requests from tourists now,” told me Douglas Munney of De Plateau Lodge. “The website and the food festival have given Bario visibility, and this is why the volume of visitors is starting to grow more steeply.”

But now there is a cloud hanging over the future of tourism and the Kelabits. It all started a few years ago when a large trans-boundary national park was being planned under a WWF-pioneered project called Heart of Borneo. Indonesia forged ahead, creating the 1.4 million hectare Kayan Mentarang National Park. But on the Malaysia side the government inexplicably changed its stated intentions in the last minute, truncating the proposed national park to the diminutive 60,000-hectare Pulong Tau National Park, and giving the rest of the forest to Samling, Malaysia’s second largest logging company.

“We didn’t know of the logging concessions before they became a fait accompli, so we didn’t have a chance to protest,” told me Joseph Balan Seling, a former member of parliament in the Sarawak local parliament. “Now we are trying to keep the loggers out of some areas, such as the hill over there.” He pointed to a slope at the edge of the Bario plateau, which is one of two 1000-hectare parcels of forest that the Kelabits are seeking to have designated as community forest.

Everyone is consternated about the logging, and mutterings of high-level corruption are rife, although no one wanted to talk openly. (This is the same place where the Swiss anti-logging campaigner Bruno Manser was presumably murdered by the loggers ten years ago.) Now, in this new wave of logging, the fear is that virtually all the land outside the national park will be stripped bare, and the government has responded to the disquiet by promising to expand the national park once logging is through, presumably on logged land. (A high proportion of timber from Borneo is exported by Samling to Europe.)

The tourism operators have already lost the Bario Loop. This used to be the most popular trek in the Kelabit Highlands, a five-day loop-trek of three villages, but now the area has been logged. Now many of the guides take tourists trekking on the other side of the border inside Kalimantan where the forest is intact.

Logging is also creeping throughout Pa Dallih, the area that has the greatest concentration of historical sites in the Kelabit Highlands, and where a team of archeologists from the University of Cambridge are currently doing research. Already, 500 historical or cultural sites have been mapped, and Sarah Hitchner, an American who’s doing her PhD on the subject, believes that there are “at least a total of 700 to 800 sites.”

“Once these historical sites are identified,” told me Jaman Riboh, a tourist guide who is involved in the mapping and management of these sites, “a buffer zone is marked around each site. The logging company does not touch anything within the buffer zones, and hence this also becomes a way to save some of the forest.”

One day I went looking for the Penan. These jungle nomads now mostly lead a semi-settled existence, and I found some of them in a settlement on the outskirts of Bario. Just beyond the last fields I found the rickety construction of Rose Melai’s family. Rose is one of the few Penan who can speak some English, and she joined me as I ventured further up the slope to the main Penan camp, which consisted of about twelve shacks built of wood and bamboo and scrap – sheets of plastic and corrugated iron, or whatever else they could scavenge in Bario. “They moved here in the hope of finding work in the Kelabits’ rice fields,” Rose explained. “It's the only way we can make money, earning 15 or 20 ringgit every day.”

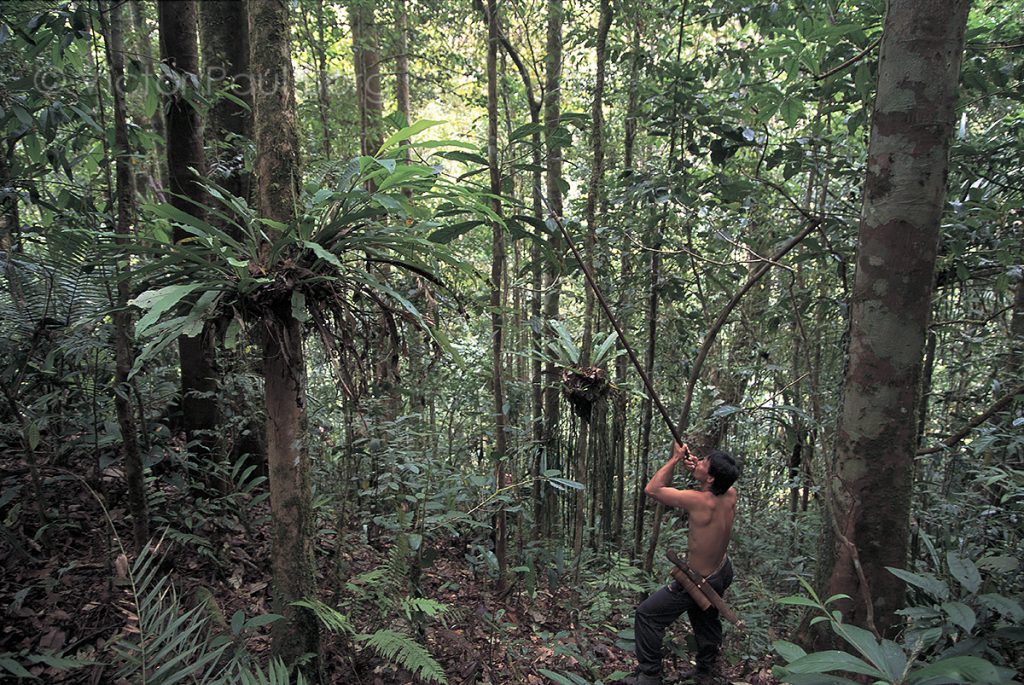

The Penan still fetch virtually all their food in the forest. Their vegetable staple is the succulent and astringent stem of the sago palm, and they hunt birds and animals with blow-pipes, smearing their darts with the poisonous sap of a particular tree. Today they were loitering at the squalid camp, and they gave Rose some papers to read. “These are government papers asking the children to go to school,” she told me. “But the Penan see no value in sending children to school.”

Rose stood apart the rest. She was better dressed (“A Kelabit woman gave me this dress because she pitied me,” Rose said) and she did send her children to school. But now she had a problem: she couldn’t afford the 300 ringgit for the reading glasses that her daughter needed.

Later I joined Rose and her husband on a hunting trip. We went off the path and into virgin forest. The man stalked animals and birds, and Rose picked rattan and other vegetable material. She could name everything in the forest – everything had a purpose, whether spiritual or edible or utilitarian. The man bagged some squirrels, and that evening, as we cooked the animals in the hut, Rose apologized for not having any drink to serve me. “Almost everything we hunt is for our consumption,” she told me. “Whenever we have money we can buy clothes and pots and coffee and sugar. But we can do without those things. We can live without money.”

At least for as long as they have forest.

© Victor Paul Borg. This article was first published in the magazine of the British Royal Geographic Society.